When preparing the National Water Sector Development Plan for Somalia in April 2025, we came upon the following dilemma:

- About 60% of the budget was allocated to rural areas and 40% to urban areas, but:

- Around 70% of Somalis live in urban centers or settlements

- 70–75% of the population is under 30, mostly literate, and aspiring to urban lives

- Perhaps 70% of Somalia’s GDP is generated in urban areas

This is a common situation today.

Most of the world population lives in urban areas and cities generate the majority of national GDP. Consequently, they also pay the most tax. Yet even though urban water demand is rising rapidly (in the global south) because of population growth, rural-urban migration, and economic development, water resource management (WRM) remains disproportionately focused on rural areas. In addition, budgets for WRM are generally inadequate and these meagre WRM budget allocations are skewed towards rural areas.

It points to two paradoxes:

- For the most part, water resources management focuses more on rural areas than on urban areas, even though urban areas generate most of the budget for WRM and require large investment in water infrastructure.

- Water is vital to life, environmental value, and socio-economic development, but society is generally not willing to make adequate funds available for its protection and management.

How can we resolve these paradoxes?

Setting the scene

Let’s first define the context.

- In urban areas, there is a difference between securing long-term water availability—on the one hand—and between producing drinking water and treating wastewater—on the other hand. The former is concerned with ensuring that adequate volumes of water of adequate quality are available now and in the future. This is the responsibility of the water resources management agency. The latter is concerned with producing drinking water of good quality and delivering it to households and businesses, and with treating the resulting wastewater so that it can be reused and does not pollute the environment. Urban water supply and sanitation are delivered by public utilities and private companies.

- Urban water supply provides an attractive business opportunity for the private sector. Domestic and industrial water is a necessity, and urban customers are willing to pay for consistent and good quality water supply. It generates steady revenue streams that are relatively resilient to economic downturns. Hence private companies are often willing to invest in water supply infrastructure (in urban areas) such as pipelines, treatment plants, and distribution networks, if granted long concessions and with some public contributions. Options for Public-Private-Partnership (PPP) are far fewer in rural areas.

- Thus, with few viable PPP options in rural areas, investments in WRM and WRM infrastructure in rural areas for the most part require a large contribution of public funds.

- However, given the huge and competing demands for government funds—for education, health, pensions, electrification, roads, etc.—expecting higher WRM budgets is probably not realistic.

- It means that it will be difficult to find the funds for the necessary investments in sustainable water resources management in rural areas. Hence other funding mechanisms need to be sought.

- The volumes of water for domestic and industrial water supply in urban areas are small compared to the water needed for food production. If necessary, water for urban water supply can be acquired through unconventional means such as desalination or deep groundwater.

- This is not the case with water for agricultural production. The huge volumes of water for producing food will come from a combination of rainfall, surface water, and groundwater. It requires careful water management, and land management by association.

- There are many interconnections between urban and rural areas. For example: rural areas provide affordable food; rural-urban migration surges in the absence of water security in rural areas, putting huge pressure on urban services and infrastructure; runoff in rural areas generates the water for urban water supply. And many more.

Resolving the paradox: creating rural-urban symbiosis

Viewing urban and rural areas as separate systems is not a practical approach. In fact, there are many interconnections and fostering stronger rural-urban linkages could resolve the two paradoxes identified above. In essence, we need to come up with a system where the urban population benefits directly from rural services and is willing to pay for them.

“The kitchen is the new gym”

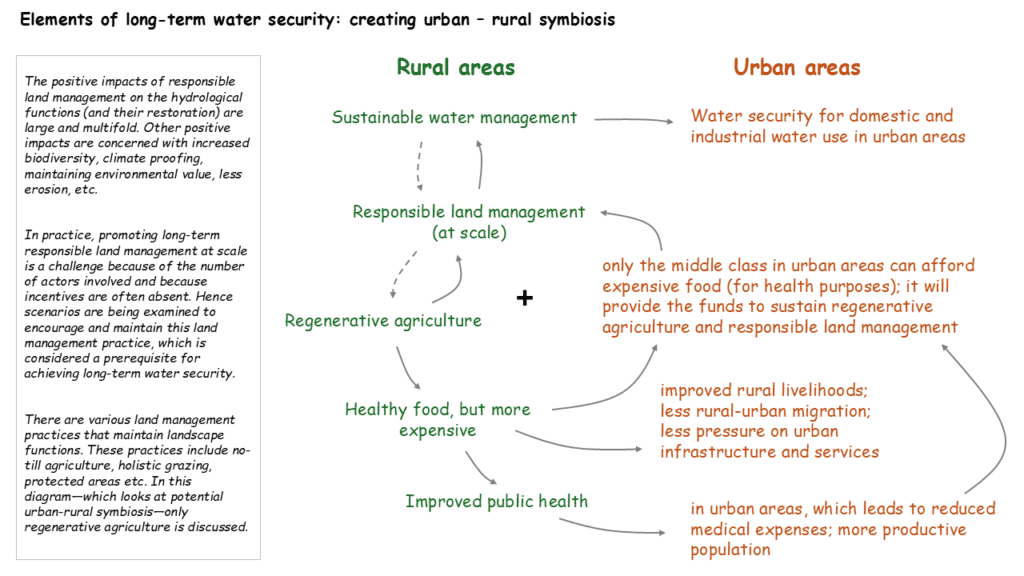

An obvious opportunity for creating this symbiosis is the agri-food system. It specifically concerns regenerative agriculture, which produces healthy food that improves public health. A poor diet comprising of highly processed food is among the main contributors to the ongoing health crisis—characterized by obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and cardio-vascular disease—in large parts of the world, though mostly in urban areas. In a video presented in a previous post, Dr. Robert Lustig estimates that some 75% of health care funds in the USA are spent on chronic disease, 75% of which is caused by an unhealthy diet.

“You either pay the farmer, or you pay the doctor”

A growing part of the burgeoning middle class (maybe 10-20% right now) values the positive health impacts of nutrient-dense and agrochemical-free food and is willing to pay for it. It creates a positive feedback-loop in which urban areas support the provision of essential services (i.e. organic fresh local food) from rural areas, which drives regenerative agricultural practices that lead to sustainable water and land management.

It is depicted in the below causal diagram.

A web of beneficial assemblies

In a contextual environment characterized by insufficient funds for WRM, long-term water security is achieved by creating a web of beneficial relations among diverse elements—rural and urban; big and small; hard and soft; natural and man-made; varied; across the landscape—that are integrated in some sort of pattern. This cluster of relations should correlate with the environmental potential and socio-economic conditions. It is referred to as a ‘beneficial assembly’.

Beneficial assemblies can be developed at all scales. Permaculture provides a blueprint for creating a beneficial assembly at a small and local scale. The rural-urban symbiosis discussed in this post represents an example of a beneficial assembly at a much higher scale. All these beneficial assemblies together create long-term water security.

Closing remarks

In a previous post I argued that paradoxes often emerge when a sub-system is being confused for the entire (overarching) system. It leads to reductionist thinking. Hence resolving paradoxes in the water sector is often achieved by interconnecting (apparent) separate systems in beneficial assemblies. The urban-rural symbiosis discussed in the post is an example. In this case, it would simultaneously resolve two paradoxes.

“How regenerative agriculture is helping small farmers grow and earn better in urban hubs.” In the video, it is estimated that some 20% of the urban middle-class in Delhi would be willing to pay for healthy food.