Water security includes protection against floods. But is it feasible to prevent flooding of all vulnerable land? The answer is “most probably not”. It would require huge investments in flood protection works in combination with a significant budget for a dedicated flood management agency or task force. These funds are usually not there.

Moreover, flood prevention may not be the best strategy.

A recurrent theme on this blog is that the capacity for water resources management (WRM)—in terms of budgets, staff, data, models, infrastructure, etc.—is inadequate in most parts of the world. This is unlikely to change, given the competition for public funds. Hence a different WRM setup is required. One that is not always based on a full understanding of the hydrological processes, does not attempt to fully control the water resources, and does not require complex management structures.

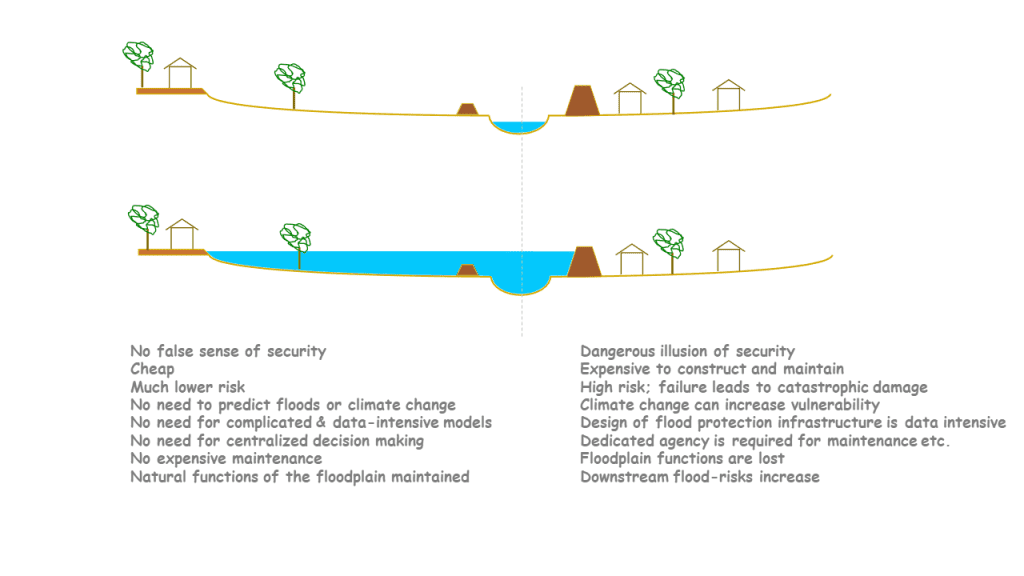

For flood management, this translates into preventing expensive flood damage rather than preventing floods.

This approach has many advantages. It does not require an accurate flood analysis; it does not provide a false sense of security—which is dangerous; it creates much more resilience against a changing climate; and it does not require hugely expensive investments in levees and related infrastructure.

Flood analysis is difficult and generally inaccurate

Flood analysis of natural rivers is difficult—or almost impossible—for several reasons:

- Flood analysis is based on the statistics of extreme events; but extreme floods are rare, and it requires at least 50 years of good quality streamflow data to fit a probability distribution; few natural rivers have complete data records of 50 years or longer

- Moreover, measurement of the actual flood is difficult and almost always inaccurate; thus, the historical extremes in the flow record are most probably incorrect—and possibly by a wide margin

- The rainfall-runoff mechanism that has produced the historic flood has probably changed due to land-use changes; these changes continue; it implies that the historic distribution of extreme events does not represents the future distribution of extreme events

- Climate change will change the intensity of extreme rain events—and probably also land-cover and rainfall-runoff mechanism; with more extreme rain, the likelihood of extreme flood events increases; it reinforces the observation that the historic distribution of flood events does not represent the future. It is likely that future flood events are more frequent and severe.

It’s an illusion to think you can predict extreme events (Nassim Taleb)

Since it is not possible, in many cases, to predict the frequency and magnitude of extreme flood events with any degree of certainty, it is best not to try. Doing so would provide a false sense of understanding and control—and is expensive in terms of data, complicated models, and qualified staff to operate these models. Better to accept that floods will happen and are probably more extreme than anticipated.

A false sense of security

Perhaps the worst situation is where levees protect against a flood level that will be exceeded someday. As memories of past flooding fade—and a false sense of security is created—large investments in property and infrastructure are made in areas that remain vulnerable to inundation. An extreme flood—which will happen at some point in time—could lead to catastrophic damage that may include loss of life. Rather than providing security, the levee has created high risks.

First reduce risks: an effective strategy to increase climate resilience

It has proven difficult to predict complex natural phenomena—such as climate change. Thus, rather than spending energy on long-term climate prediction, it is more effective to focus on minimizing the potential damage of extreme weather. Decreasing downside (risk of damage) is the first step towards climate resilience.

A sensible approach: living with the river

A sensible approach is to maintain the river’s floodplain in places where it is least harmful (most areas) and only protect important economic assets (towns & cities). Urban areas should be protected very well, for instance with flood defenses that can withstand a 5000-year flood or more.

This proposition is inspired by the “Room for the River” approach implemented in the Netherlands and follows the bimodal (barbell) strategy suggested by Nassim Taleb.

The very productive floodplain can be used for agricultural activities but not for residential purposes. Permanent housing and critical infrastructure are located outside the floodplain, or on elevated land (mounts) that is created inside the floodplain.

The floodplain maintains its natural functions such as replenishing groundwater, buffering flood-waves, and supporting rich and diverse environmental value. Floods continue to deposit fertile sediment.

Government responsibility and policy measures are limited to zoning and prohibiting permanent structures in the floodplain.

The advantages are multifold:

- No time and money spent on forecasting events that cannot be predicted

- No damage if the flood is higher than anticipated

- More resilience against the impacts of climate change

- No money spent on flood defenses that are probable inadequate

- No large investment in areas that are not safe

- Natural floodplain functions are maintained

- No need for centralized agencies

- No need for expensive maintenance

- No management decisions are necessary; the system will self-regulate ( for instance, people will avoid building houses in an area that inundates every few years, while finding a way to use the area productively)

The main disadvantage is that the use of the productive and attractive floodplain is limited by occasional floods. But this can be remedied to some extent with a bit of creativity and is a reasonable price for a very resilient system.

Note: flood protection in a regulated river will probably be different. Specifically, an alternative flood management strategy can be pursued for rivers with upstream reservoirs—which can buffer part of the flood-wave.

(with thanks to: Nassim Nicholas Taleb: Antifragility—Things That Gain from Disorder; Random House, 2012)